The placenta was found on an ultrasound scan to be on the anterior uterus wall and was not low lying. The umbilical cord had a velamentous insertion into the placenta and blood vessels were seen in the membranes covering the cervix.

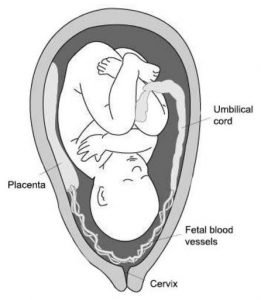

Velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord is when the umbilical cord blood vessels (carrying the baby’s blood to and from the placenta) run in the fetal membranes from the cord to the placenta. The exposed vessels are not protected by Wharton’s jelly and hence are vulnerable to rupture. This is especially so if the exposed vessels cross the cervix, the most likely spot for the membranous sac to rupture. When the exposed and unprotected vessels are in the membranes covering the internal cervical os the condition is called vasa praevia.

When there is rupture of the membranes there can be tearing of these unprotected foetal vessels and loss of baby’s blood. Loss of 100 ml of baby’s blood can lead to hemorrhagic shock and death. This can happen within a few minutes of the vessels tearing. Vasa praevia occurs in about 2.1 per 10,000 women giving birth1

I discussed the diagnosis and its possible implications in detail with Ashley and her husband. We also discussed management options.

The ultrasound scan was repeated at 28 weeks pregnant. The placenta was reported as anterior and not low lying. The inferior margin was at least 49mm from the internal os (cervix). The umbilical cord insertion into the placenta was reported as velamentous with vessels coursing the inferior margin of the placenta along the lower anterior wall and onto the posterior uterine wall for a distance of 82mm, resulting in vasa praevia with vessels crossing directly over the internal cervical os. Management options were again discussed.

There is no consensus view in the medical literature about pregnancy management, except almost all articles suggest delivery should be by Caesarean section before the onset of labour and before rupture of membranes. I suspect that is because vasa praevia is such an uncommon condition and there no clinical proof that any one approach to pregnancy care gives a better outcome. The medical literature does suggest it is the antenatal diagnosis of vasa praevia that is the most important determinant of outcome.

The concern was the potential gravity of spontaneous rupture of membranes. If this happened and baby’s blood vessels in the membrane were also torn then the outworking of this could be exsanguination of the baby. The time between tearing of the foetal blood vessels and exsanguination could be only minutes. So while the popular management view that a patient with vasa praevia should be admitted to a public hospital with a level 3 neonatal nursery from about 30 weeks pregnancy had logic, the time period from diagnosing foetal haemorrhage from tearing of foetal blood vessels and delivery of the baby by Caesarean section may be too long, even if she was an inpatient. The outcome in such a situation could still be the death of a baby or baby living with the devastating consequences of lack of oxygen, including permanent brain damage. Furthermore, I could not find, in the medical literature, clinical evidence or anecdotal case reports where this approach of prolonged hospitalisation made a difference in the outcome. As well Ashley did not like the idea of lying in a public hospital bed for weeks. So we decided on careful outpatient management. Ashley would stay close to her home, which was located close to the hospital. She would do minimal activities and avoid sexual intercourse. She would notify if any awareness of uterine contractions and especially if concern about possible rupture of membranes or if she had any vaginal bleeding. We also decided on early delivery with steroid cover to help mature baby’s lungs and minimise the risk of the baby having breathing problems after birth (Hyaline Membrane Disease, which is also called Respiratory Distress Syndrome).

The Caesarean section went ahead as planned at 34 weeks and 5 days gestation. The operation was done under a spinal anaesthetic. Her son Noah was born in good condition and had a good birth weight of 2710gms. Both velamentous insertion of blood vessels into the placenta and vasa praevia were confirmed after delivery of her baby. See photo adjacent.

Postnatally mother and baby did well. Noah did not have any breathing problems but did have other issues of prematurity. Initially, his blood sugar level was unstable and then there were feeding and jaundice issues. Otherwise the mother and baby have done well.

A good article on vasa praevia was published this year titled ‘Vasa Previa Diagnosis, Clinical Practice, and Outcomes in Australia1’. The authors considered hospitals in Australia with greater than 50 births per year between May 1, 2013, and April 30, 2014, where women were diagnosed with vasa previa during pregnancy or at childbirth.

This report states 63 women had a confirmed diagnosis of vasa previa in Australia in the one year the study time period. The estimated incidence was 2.1 per 10,000 women giving birth. 58 women were diagnosed antenatally and all had a Caesarean section delivery. There were no baby deaths in women where vasa praevia was diagnosed antenatally. For the five women with vasa previa not diagnosed antenatally, there were two baby deaths with a case fatality rate of 40%. The conclusion was: ‘The outcomes for neonates in which vasa previa was not diagnosed prenatally were inferior with higher rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Our study shows a high rate of prenatal diagnosis of vasa previa in Australia and associated good outcomes.’

This study and other studies show that the most important determinant of a good outcome with vasa praevia is diagnosis during the pregnancy. The most likely time vasa praevia will be suspected is with the 19-week foetal morphology scan. Logically, there will more accuracy in making this very important diagnosis if this morphology scan is done by a specialised pregnancy ultrasound unit, as was the case for Ashley.

Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;130(3):591-598. Vasa Previa Diagnosis, Clinical Practice, and Outcomes in Australia.Sullivan EA1, Javid N, Duncombe G, Li Z, Safi N, Cincotta R, Homer CSE, Halliday L, Oyelese Y.

For more information, have a chat with us on 02 9680 3004 or contact us today.