It was Louise’s second pregnancy. In her first pregnancy, she went into spontaneous labour at 40 weeks and 6 days. She had a spontaneous vaginal delivery of a baby girl weighing 3662gms.

This second pregnancy was progressing well except her baby started measuring large for dates in the third trimester. At 38 weeks and 4 days, her baby was estimated by an ultrasound scan to have a weight greater than her first baby’s birth weight. At 38 weeks and 4 days, her baby’s weight was estimated to be 3840gms. I saw her the next week and the baby had an estimated weight of 4119gms. The onset of labour was not imminent. We discussed whether we should wait for the onset of labour or book a day for labour to be induced. While ultrasound scan estimate of weight is only approximate, the baby was appearing to be (both by scan and abdominal palpation) a generous size and by waiting for the onset of labour the baby would only get even bigger. This larger size would make it more difficult for her to have a normal vaginal delivery and there would be an increased risk of the shoulders of the baby getting stuck (called shoulder dystocia). We decided on induction of labour to avoid the baby getting larger.

Labour was induced two days later when Louise was 39 weeks and 5 days pregnant. Louise had a spontaneous vaginal delivery of a baby girl weighing 3924gms. There was shoulder dystocia which I was able to successfully manage without her daughter suffering any trauma. Louise had an intact perineum.

While the ultrasound estimate of weight was 195gms greater her baby’s actual birth weight, her baby’s actual birth weight was 262gms greater than her first baby’s birth weight (second baby was born 9 days earlier than her first). Had Louise’s pregnancy continued, assuming she went into labour at 40 weeks 6 days (viz. same time as first delivery), the projected second baby’s birth weight would have been greater than 4300gms (assuming continued in-utero growth at the same rate). It was likely that by continuing the pregnancy it would have resulted in a challenging vaginal delivery, especially as there was shoulder dystocia with a 3942gms birth weight baby.

I am a great believer in the approach to ‘do a little bit of intervention to avoid needing a lot of intervention’. Louise and I agreed it was very worthwhile to intervene in her pregnancy by induction for labour rather than the likelihood of having a larger baby to delivery. A larger baby implied an increased likelihood of:

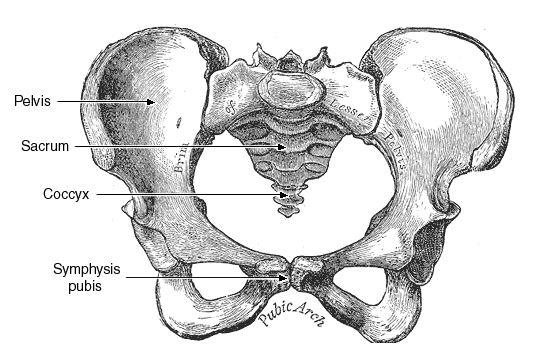

- cephalopelvic disproportion (baby’s head is too large to fit through the mother’s pelvis). In first stage labour, this would result in a Caesarean section delivery and in second stage labour either an operative vaginal delivery or Caesarean section delivery,

- maternal trauma (episiotomy and/or significant tearing),

- baby trauma (because of shoulder dystocia or operative vaginal delivery instrumentation),

- postpartum haemorrhage.

It is all about mechanics. The bony head of the baby must be able to transit through the bony birth canal for a vaginal delivery to take place. If the pelvis is too small or has an unusual shape or baby’s head is too large or has an unusual shape or is more deflexed (so a larger diameter is presenting, as with an occipito-posterior position) then the chances of a spontaneous normal delivery happening are reduced. A greater concern than the head getting stuck in the birth canal is having the head deliver and the baby’s shoulders are too bulky for them to deliver. This is called shoulder dystocia. Baby is no longer getting any oxygen once the head is out until the body delivers. There are various manoeuvres that an obstetrician can use to manage shoulder dystocia but they can be risky for the baby.

It is all about mechanics. The bony head of the baby must be able to transit through the bony birth canal for a vaginal delivery to take place. If the pelvis is too small or has an unusual shape or baby’s head is too large or has an unusual shape or is more deflexed (so a larger diameter is presenting, as with an occipito-posterior position) then the chances of a spontaneous normal delivery happening are reduced. A greater concern than the head getting stuck in the birth canal is having the head deliver and the baby’s shoulders are too bulky for them to deliver. This is called shoulder dystocia. Baby is no longer getting any oxygen once the head is out until the body delivers. There are various manoeuvres that an obstetrician can use to manage shoulder dystocia but they can be risky for the baby.

There is the possibility of the baby sustaining permanent brachial nerve damage (and a limp arm) or of the baby’s body not being able to be delivered and baby dying (half delivered – head out and body in). The risks associated with shoulder dystocia are greater if the person doing the delivery is a midwife or inexperienced doctor. Avoiding the baby getting too large increases the likelihood of a good outcome for mother and baby, as was Louise’s experience.

There is the possibility of the baby sustaining permanent brachial nerve damage (and a limp arm) or of the baby’s body not being able to be delivered and baby dying (half delivered – head out and body in). The risks associated with shoulder dystocia are greater if the person doing the delivery is a midwife or inexperienced doctor. Avoiding the baby getting too large increases the likelihood of a good outcome for mother and baby, as was Louise’s experience.

Over the years I have adopted this approach of early induction of labour many times with success. I have also done so on many occasions for patients who have had a more difficult vaginal delivery in the past and are keen to avoid both repetition and to avoid a Caesarean section.

Early induction of labour is not always an option. If the cervix is closed, long and firm and the head of the baby is high at 40 weeks (especially in the first ongoing pregnancy) there is a considerable likelihood that there will be a failed induction attempt that results in a Caesarean section. Indeed, the usual reason for these findings is the baby is too big for the birth canal. I don’t mind attempting an induction of labour in this context (if this is the patient’s preference) with the patient fully aware of the situation and mentally prepared for the possibility of the induction not working out and after considerable hours of ripening the cervix is still closed.

There are patients where I recommend in the pregnancy that they would be safer with an elective Caesarean section. This could be because of a history of pelvic bone trauma in the past, known to have a compromised pelvic shape or size, had a very concerning traumatic vaginal delivery in the past (and so is frightened to attempt a vaginal delivery this time), had major vaginal trauma or a significant third-degree tear or a fourth-degree tear with a previous delivery or being unusually short (implying a small pelvis).

In some cases, it is appropriate to do a CT pelvimetry check of the woman’s pelvis in advanced pregnancy to check the size and shape of the bony pelvis. A good quality CT scan should be very accurate. We do not have the same degree of accuracy with checking the size of the baby’s head by ultrasound scan. Also, the head size presenting will be greater if the head is deflexed such as with an occipito-posterior position baby.

When we are concerned that the baby may be too large for the pelvis we use the term ‘trial of labour’. The pregnant woman knows the risks and if labour progress does not go well because of cephalopelvic disproportion she is mentally prepared.

Cephalopelvic disproportion and shoulder dystocia can occur when there is normal-sized pregnant woman with a normal-sized unborn baby. It can happen even though the pregnant woman has been successful in having spontaneous vaginal deliveries in the past. Despite the pregnant women being of normal size, she may have a smaller or unusual shaped pelvis so the pelvis cannot accommodate her normal-sized baby. It also may be that so has a normal size and shape pelvis but the baby’s head is large or deflexed so a larger diameter of the head is presenting. It could be that this baby’s size (while in the normal range) is bigger than her previous babies and is too big for her pelvis.