Paula’s first pregnancy was managed as a public patient.

She told the first time we met my management of her second pregnancy that a short cervix had been diagnosed in her first pregnancy at 23 weeks gestation. She said she was kept in hospital on bed rest for 5 weeks. Progesterone pessaries were administered daily. She was then allowed to go home and to continue bed rest at home. She developed hepatic cholestasis and so her labour was induced at 37 weeks 5 days gestation. Total duration of labour was 5 hours. She had a forceps delivery. There was third degree tear and a postpartum haemorrhage. She was given four units of blood.

hospital on bed rest for 5 weeks. Progesterone pessaries were administered daily. She was then allowed to go home and to continue bed rest at home. She developed hepatic cholestasis and so her labour was induced at 37 weeks 5 days gestation. Total duration of labour was 5 hours. She had a forceps delivery. There was third degree tear and a postpartum haemorrhage. She was given four units of blood.

She was nervous about the implications for this, her second, pregnancy. I advised her that her induction at 37 weeks and a 5 hour labour was not consistent with her having cervical incompetence. Furthermore, that was nothing in her history that would predispose her to cervical incompetence. She did not want prolonged hospitalisation and bed rest this time. I advised her I could do cervical cerclage procedure, prescribe progesterone pessaries or arrange regular scans to check for cervical shortening. She decided on the latter.

She had cervical assessments done at ultrasound unit which specialises in pregnancy ultrasound scans at 14 weeks, 18 weeks, and 23 weeks gestation. At each scan there was no concern about the cervix which remained closed and measured 35 – 36 mm long (normal length). We decided not to do any further cervical scan checks. She is now 37 weeks gestation and is scheduled for an elective Caesarean section in just under 2 weeks time. She is very well. There is no hepatic cholestasis. The Caesarean section is because of her history of a third-degree tear and as well her anxiety about having another labour, vaginal delivery and perineal tearing in view of what happened last time.

Paula’s doctors in her previous pregnancy were worried that she had cervical incompetence. I don’t believe she had cervical incompetence.

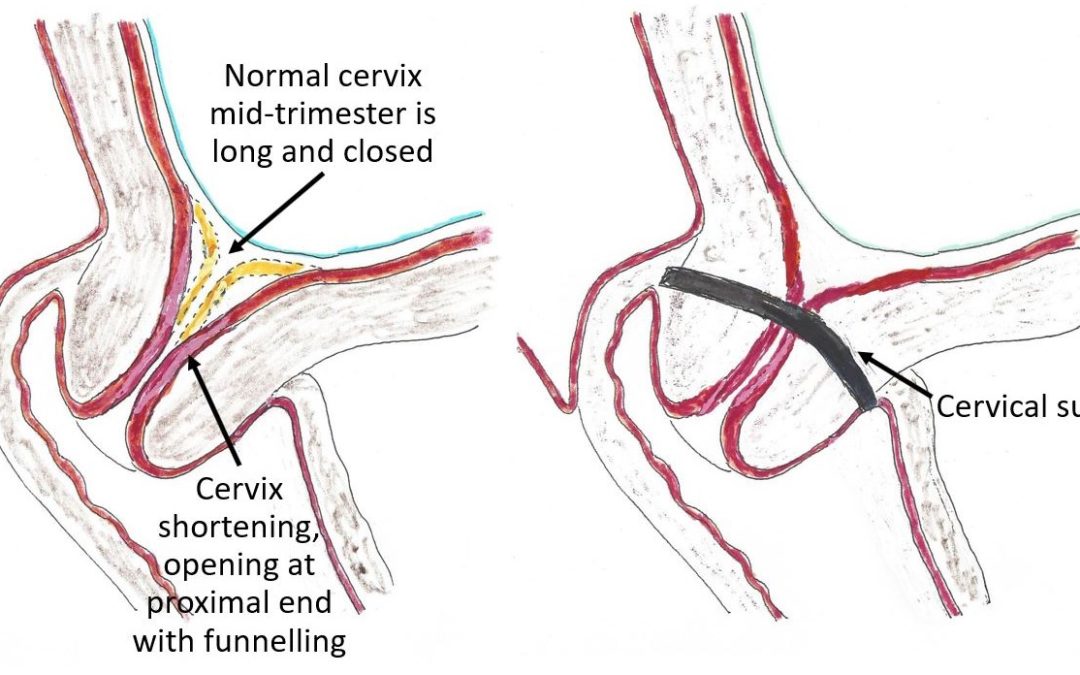

Cervical incompetence is defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) as the inability of the uterine cervix to retain a pregnancy in the second trimester, in the absence of uterine contractions. Cervical incompetence will result, if untreated, in preterm delivery. The simplest way of understanding cervical incompetence is to think of the cervix when incompetent as being ‘weak’ and as the uterus enlarges and puts more pressure on the cervix the cervix opens (without being in labour).

The cervix is composed of both muscle and fibrous connective tissue. The fibrous component is responsible for the tensile strength of the cervix. Cervical incompetence is thought to be related to a structural defect in tensile strength.

Cervical incompetence is usually acquired but may be a congenital problem. The most common congenital causes are a defect in the embryological development of Mullerian ducts, in utero exposure of the pregnant woman’s mother to diethylstilbesterol (DES), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome.

The most common acquired causes are cervical trauma such as cervical lacerations during childbirth, cervical conization, LLLETZ (loop excision transformation zone of cervix) procedures and forced cervical dilatation during the uterine evacuation in the first or second trimester of pregnancy for miscarriage or termination of pregnancy. The risk compounds if more cervical risk procedures are done.

In many women, the cause of cervical incompetence is unknown.

Cervical incompetence is over diagnosed today.

In the past the concern about cervical incompetence was based in a woman’s history. If she had one or multiple acquired causes listed above, or a congenital risk factor listed above there was close cervical monitoring as there was increased risk of cervical incompetence. If she gave a history consistent with cervical incompetence in her previous pregnancy (painless cervical dilatation and bulging foetal membranes upon presentation in the second trimester of pregnancy, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), rapid delivery of a very preterm infant, rare or absent uterine contractions in labour) then cervical incompetence was highly suggested and usually the cervix was treated with a cervical cerclage procedure.

As a consequence, obstetricians in the past were treating far fewer pregnant women for cervical incompetence than today. The incidence of cervical incompetence has not increased. The suggested likelihood has increased.

In the past ultrasound scans were not routinely done in pregnancy. That is because there were not the ultrasound technological advances that we have now. Now morphology (or foetal anatomy) ultrasound scans at about 20 weeks are a routine part of pregnancy management. A cervical assessment is routinely done as part of this ultrasound assessment. The cervical assessment reports the cervical length and if the cervix is closed. If the cervix is diagnosed as unusually short the obstetrician is usually advised by a phone call. The obstetrician then sees the patient to discuss the ultrasound scan findings.

The challenge for the obstetrician when seeing the patient is what to do next. That is because a short cervix does not usually mean an incompetent cervix. The ultrasound scan findings are discussed, and the patient advised of the increased risk of cervical incompetence because her cervix is short. She is told if there is cervical incompetence then it is likely there will be a very preterm (before 30 weeks) delivery. Baby will be at risk of not surviving if the delivery is very preterm. Otherwise, there are all the risks and challenges of managing a very preterm newborn and the long-term implications for baby’s health. Options of management are discussed. These are doing nothing and close monitoring with serial ultrasounds scans of the cervix, daily progesterone pessaries or cervical cerclage. Prolonged bed rest is not of proven benefit.

The challenge of serial ultrasound scan’s is the discomfort, embarrassment it is to some women, the cost and if there is significant cervical change between scans it will be riskier to insert a cervical suture and the stitch is less likely to be effective. Progesterone pessaries are reported to help but in my experience, there has been ongoing shortening if there is cervical incompetence. I have never had an issue with inserting cervical sutures and all my patients who have had cervical sutures have continued their pregnancies to at least 37 weeks gestation. There is a slight risk of intrauterine infection in the pregnancy after the stitch has been inserted. I therefore prescribe prophylactic antibiotics until after the stitch is removed.

Sometimes pregnant women have early foetal anatomy scans at 12 weeks. This gestation is a little too early to detect most cases of a short cervix. If a ultrasound scan is done at 14 weeks it can check for cervical incompetence. But a normal appearing cervix at 14 weeks does not exclude cervical incompetence as it may not be manifest until a later gestation..

There are other reasons for early preterm delivery as such placental abruption, intrauterine infection and maternal severe trauma and if another reason was the cause a cervical cerclage procedure next pregnancy was not appropriate management. If a woman has a cervical suture in situ and goes into preterm labour the cervical stitch needs to be removed to avoid cervical trauma.

Cervical incompetence has become a medico-legal matter. If the patient does have cervical incompetence and it is not diagnosed and treated, she may blame the ultrasound doctor and her obstetrician. It is tragic to lose a baby and so her upset and vindictive attitude can be understood. When faced with the possible diagnosis of cervical incompetence she usually decides on the side of caution as she does not want to put her baby at risk. As a consequence, obstetricians are treating far more women for cervical incompetence that in the past.

Most short cervices are not incompetent cervices and so most women are being treated unnecessarily. I tell a patient when I treat her cervix that her short cervix may not be incompetent. I tell her we will know if she has an incompetent cervix after I remove the cervical suture at 37 weeks. If within a couple of days, she is back in birth unit with spontaneous rupture of membranes or labour and she has a quick and less painful in first stage labour than usual then it is likely she had cervical incompetence. If I end up inducing her at 41 weeks, she still has a reasonably long cervix at the onset of labour and has a normal duration and pain in labour then it is likely that there is not a cervical incompetence problem. What is interesting that even when this happens and I tell her that her cervix is not incompetent often a woman will decide for cervical suture in the next pregnancy ‘just in case”.