This article is for my patients who have had a Caesarean section and are considering attempting a VBAC delivery this time. It’s purpose is to give you comprehensive information to help you to make your decision whether or not to attempt a VBAC. The contents of this article are to be used as background information only on this topic and are to be used in conjunction with consultation with me.

What’s the greatest risk of an attempting a VBAC?

Having a Caesarean section does have implications for the next delivery. The biggest concern of an attempt at a vaginal birth after a Caesarean section (VBAC) is rupture (tearing / splitting) of the uterus in labour.

Historically attempting a VBAC has been called a ‘trial of scar’ labour. This trial of scar terminology more accurately describes the concern of a labour after a Caesarean section delivery. The labour is a ‘trial’ to see if the scar remains intact and doesn’t tear.

Why is there an increased risk of uterine rupture with an attempt at a VBAC?

Healing of the previous Caesarean section uterine cut will result in scar tissue forming along the line of the uterine cut. This is unavoidable and is a normal phenomenon of healing. Scar tissue will not form if the previous delivery was vaginal and not a Caesarean section because with a vaginal delivery there is no cutting of the uterine muscle.

Healing of the previous Caesarean section uterine cut will result in scar tissue forming along the line of the uterine cut. This is unavoidable and is a normal phenomenon of healing. Scar tissue will not form if the previous delivery was vaginal and not a Caesarean section because with a vaginal delivery there is no cutting of the uterine muscle.

In labour, the uterine muscle contracts to cause the cervix to dilate and thin out (‘effacement’) and at the same time to ‘squeeze’ the baby into the birth canal. When the cervix is fully dilated ‘first stage’ labour ends and ‘second stage’ labour begins. Contractions in second stage labour, with the help of maternal pushing, are to move the baby down through the birth canal and out through the vaginal entrance.

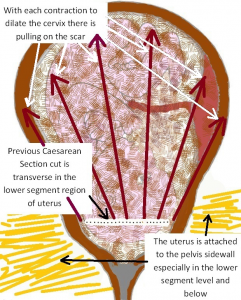

The scar tissue from the previous pregnancy uterine cut is located horizontally across the lower aspect of the anterior uterine wall, in an area called the ‘lower segment’ of the uterus. The uterus is especially attached to the pelvic support tissues at this level. There is a maximum intensity of contractions of the uterus at this level to cause the changes above that are necessary for a vaginal delivery. See diagram adjacent.

With each contraction there is ‘pulling apart’ tension put on the uterine scar tissue. Scared tissue is never as strong as non-scarred tissue, and so there is an increased risk of uterine rupture along the scar line because of the scar tissue. The scared uterine wall is either strong enough to remain intact during labour and delivery or else it tears or so there is uterine rupture. Whether the uterus scar tears apart, and if it does so when in labour it will tear, is totally unpredictable.

The risk of the uterus tearing in advanced pregnancy and before labour is much less than in labour. If it tears in pregnancy before the onset of labour it is because of stretching of the uterus by baby in the amniotic fluid sac.

Sometimes when I do a repeat Caesarean section I find the lower segment of the uterus very thin and in extreme cases it paper thin and transparent. Very occasionally I have seen the baby in the amniotic fluid sac through a very thin transparent uterine wall. When this is the case I am are so pleased I am doing a repeat Caesarean section rather than the patient attempting a VBAC, as it would be highly likely with contractions that the paper-thin uterine wall would split. I had one patient where I was so concerned about the thinness of her uterine wall at her third Caesarean section that I advised her it was too dangerous to have a fourth baby.

What are the implications of a ruptured uterus?

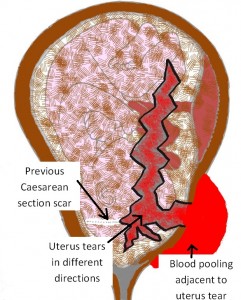

For you. What damage uterine rupture causes you depends on how severe the uterine tear is and where it is located. As well as a tear in the uterine wall the tear can extend and can result in trauma to major internal organs (bladder and bowel) and to major blood vessels (such as the uterine artery) which will result in life-threatening internal haemorrhage.

For you. What damage uterine rupture causes you depends on how severe the uterine tear is and where it is located. As well as a tear in the uterine wall the tear can extend and can result in trauma to major internal organs (bladder and bowel) and to major blood vessels (such as the uterine artery) which will result in life-threatening internal haemorrhage.

Recently a woman in the care of another obstetrician had to have many units of blood because of life-threatening internal haemorrhage following a uterine rupture.

For your baby. Whether your baby will be affected is unpredictable. A common sign of uterine rupture is foetal distress. If the blood flow to the baby is reduced by the uterine rupture, the rupture will result in reduced oxygenation or even cessation of oxygenation to the baby. Your baby can suffer organ damage including permanent brain damage and even in death because of severe lack of oxygen.

Occasionally a woman can have a ‘silent’ rupture. That usually is only a small tear. With a silent rupture, there is no impact on her wellbeing or the baby’s wellbeing and no symptoms/awareness of the uterus having ruptured in labour or with delivery.

Suspicion of a ruptured uterus in labour will always need very urgent surgery to deliver your baby and assess and deal with internal damage in you.

This surgery is almost always done under a general anaesthetic because of the gravity of the situation. Necessary surgery to correct damage can be very major and very high risk and may even involve the need for an emergency hysterectomy. This is one of the most dangerous hysterectomies possible because of the circumstances.

Incidence of a ruptured uterus

The generally stated incidence of a uterus rupturing in labour after a Caesarean section is about 1 in 200 cases, although the incidence in studies I have seen reported varies from 1 in 70 to 1 in over 300. The implied risk will vary according to circumstances and be greater for some women than others.

Impact of having a previous successful VBAC. This incidence of uterine rupture and risk of uterine rupture does not decrease if you have had a successful VBAC prior to this current pregnancy. A successful VBAC will increase the likelihood of you having a more efficient and quicker labour and a spontaneous vaginal delivery rather than an operative vaginal delivery.

Increased risk of uterine rupture

The risk of a uterine rupture increases in the following circumstances:

- Previous classical or vertical lower uterine segment incision.

- Previous myomectomy (fibroid removal).

- Previous rupture or perforated uterus at a gynaecology operation.

- More than one previous Caesarean section.

- Labouring less than 18 months since the previous Caesarean section.

- Morbid maternal obesity (BMI (Body Mass Index) >40).

- Foetal weight > 4 kg.

- Contracted (small) pelvis.

- Labour with other than a cephalic (head down) presentation of baby.

- Poor uterus cut surgical closure technique of the obstetrician who did the previous Caesarean section.

- Poor healing of the previous Caesarean section uterus cut.

- Induction of labour.

- Augmentation of labour if you have slow progress in labour.

Diagnosis of a ruptured uterus

Unfortunately whether or not your uterus will rupture cannot be predicted.

Uterine rupture occurs without warning and is a retrospective diagnosis.

Occasionally an ultrasound when you are not pregnant will report a uterine wall defect in the area of the scar. Sometimes in advanced pregnancy an ultrasound scan will report a very thin lower uterine segment, which implies increased risk.

There are extra precautions in an attempted VBAC labour to diagnose uterine rupture ASAP. Delay in diagnosis and appropriate care will put your and your baby’s wellbeing at increased risk. The extra precautions include close monitoring of your wellbeing by the nursing staff and continuous foetal heart rate monitoring (CTG) of your baby. Foetal distress often is the first sign of uterine rupture.

While continuous CTG monitoring may not be your preference as it will restrict your mobility in labour, it is a widely held management prerequisite of attempting a VBAC. If your uterus ruptures when your baby is not being monitored there can be a delay in diagnosis which will increase the risk to you and your baby.

Other signs of uterine rupture that we watch for and that you and your husband/partner should report to the nursing staff immediately if they occur in labour are vaginal bleeding, severe sharp pain of sudden onset, a sudden cessation of contractions, and becoming faint or even going unconscious (because of low blood pressure with internal bleeding).

Sometimes the rupture is silent and happens without any signs or concern about your or your baby’s wellbeing.

Management of attempting a VBAC labour

Prelabour

If you have had a previous Caesarean section and request attempting a VBAC delivery this time please advise me during your pregnancy.

I will assess your suitability in advanced pregnancy. If any of the ‘Increased risk of rupture’ circumstances 1 – 10 (see above) are relevant then I will advise you that it is unsuitable for you to attempt a VBAC, as it is too dangerous for you and your baby.

If none of the ‘increased risk of rupture’ circumstances 1 – 10 apply then I will assess your suitability for an attempt at a VBAC in the last weeks of your pregnancy by both a pregnancy ultrasound scan (to check the baby’s size (circumstance 7) and position and whether there is concern about your Caesarean section uterine scar) and a CT pelvimetry scan (to check your pelvis is of appropriate size and shape for a vaginal delivery (circumstance 8)).

I will discuss attempting a VBAC with you in detail including giving you copy of this document, so you understand risk and management. Doing this also means you are giving ‘informed consent’ for attempting a VBAC procedure. You are advising me with good knowledge of attempting a VBAC’s implied risks and extra management considerations that you want to have an attempt at a VBAC rather than an elective Caesarean section.

Spontaneous onset vs induction of labour. If suitable for an attempt at a VBAC it is preferred you went into spontaneous labour doing the daytime of a weekday at or before 40 weeks gestation.

If this is not the case then I will do an internal examination to assess your suitability for induction of labour. Labour induction increases the risk of uterine rupture (‘increased risk of rupture’ circumstance 11). Induction will only be considered if your cervix is ‘favourable’ for induction and it will be an ‘easy’ induction. Otherwise I will advise you it is safer for you to have an elective Caesarean section.

Time of day. An argument in favour of induction is that induction increases the likelihood of you labouring and delivering in the daytime or early evening on a weekday. To have a ruptured uterus in the middle of the night or on a weekend is much more dangerous than if it occurs in the daytime on a weekday. There are minimal staff on duty at night and on weekends and there is likely to be greater delay in doing an urgent Caesarean section as the theatre staff, anaesthetist and paediatrician will need to come into the hospital from their homes. This extra time of delay between diagnosis and delivery may compromise you and/or your baby’s wellbeing.

Going overdue. It is generally accepted that going ‘overdue’ increases the risk of labour for both you and your baby. The risks gradually increase the more overdue you go. Going overdue is associated with an increased incidence of foetal distess and even foetal death, because of deteriorating placental function. On opposite hand going overdue is associated with having a larger baby and more risk of an obstructed labour. If you have a scarred uterus having a large baby and an obstructed labour implies increased risk of uterine rupture.

In labour

Intravenous fluids, blood collection and oral intake. Placement of an intravenous line is advisable in attempting a VBAC labour. Blood is taken for blood group and antibody screen in preparation for cross match in case urgently needed for a blood transfusion. Oral intake is restricted to clear fluids because of a greater than normal probability of needing an immediate laparotomy / Caesarean section under general anaesthesia.

Assessment of progress in labour and management of failure to progress. Attempting a VBAC labour mandates vigilant assessment of progress in labour with vaginal examinations at least four hourly in the active phase of labour and more frequently as full dilatation approaches. The cervix should dilate at least at 1cm per hour in the active phase of labour and second stage should not exceed an hour in duration, unless birth is imminent.

Augmentation of labour would only be considered with great caution. A common reason for lack of progress in labour is a relative disproportion between the size of the baby and the size of your pelvis. To increase the strength of your contractions by a Syntocinon infusion to try to overcome this can increase considerably the risk of your uterus rupturing. (‘increased risk of rupture’ circumstance 12).

Foetal Monitoring. Continuous CTG monitoring throughout labour. The reason for this is explained above in the ‘Diagnosis of a ruptured uterus’ section.

Epidural. An epidural will not increase the risk of you having a ruptured uterus. Some obstetricians will not allow an epidural in labour as they believe an epidural can mask signs of uterine rupture. Sudden sharp pain over the scar is a sign of tearing and this can be missed if there is an epidural. Personally, I am happy for you to have an epidural in labour if that is your preference.

Delivery

The aim is for a spontaneous vaginal delivery without stitches. But there cannot be prolonged pushing in second stage labour, as this increases the risk of the scar tearing. As a consequence there is a higher incidence of operative vaginal deliveries (forceps and vacuum) in patients who attempt a VBAC than otherwise, especially if you have not had a spontaneous vaginal delivery prior. An operative vaginal delivery is associated with a higher incidence of perineal and vaginal trauma (including episiotomy and tearing).

Post labour

If all goes well and you are successful in having a VBAC I will do an internal examination to assess the integrity of your Caesarean section scar. You may have had a silent uterine rupture. The scar is in the lower aspect of the anterior uterine wall. This examination needs to be done immediately after delivery of the placenta to get access. Without an effective epidural it is an uncomfortable but necessary examination.

Success of attempting a VBAC

The largest study I have seen has been reported recently in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology titled ‘Vaginal birth after Caesarean section: a cohort study investigating factors associated with its uptake and success’ by HE Knight, I Gurol-Urganci, JH van der Meulen, TA Mahmood, DH Richmond, A Dougall, DA Cromwell (BJOG Volume 121, Issue 2, pages 183–192, January 2014). Of the 143,970 women in the study who had had Caesarean sections, 75,086 (52.2%) attempted a VBAC for their second birth. Younger women, those of non-white ethnicity and those living in a more deprived area had higher rates of attempted VBAC. Overall, 47,602 women (63.4%) who attempted a VBAC had a successful vaginal birth. Women who had an emergency Caesarean section in their first birth had a lower VBAC success rate, particularly those with a history of failed induction of labour requiring a Caesarean section.

The conclusion was that overall just over one-half of women with a history of Caesarean section who were eligible for a trial of labour attempted a VBAC for their second birth. Of these, 63.4% successfully achieved a vaginal delivery. Overall 33.1% of the 143,970 women who had a previous Caesarean section were successful in having a VBAC.

Women who attempted a VBAC and were unsuccessful had emergency Caesarean section deliveries. This would have been for indications including lack of progress in labour, foetal distress in labour, suspected rupture of uterus and rupture of uterus.

Norwest Private Hospital reported in the 12 months from 1st May 2016 to 30th April 2017 62% of women who attempted VBAC deliveries were successful. 38% of women who attempted VBAC deliveries required emergency Caesarean section deliveries.

Change in community attitude

More women are choosing to have elective Caesarean section deliveries than attempting a VBAC than historically was the case.

I suspect there are a number of factors behind this decision:

- Caesarean sections are much safer now than they were in the past. In the past it was safer to attempt a VBAC (with its implied risk) than have a Caesarean section delivery. Today an attempt at a VBAC has much more risk for the woman and her baby than an elective Caesarean section.

- Most pregnant women are less likely ‘to take risk’ than they did in the past. This is shown also in the attitude of most pregnant women to ‘high risk’ nuchal translucency scan results. When a nuchal translucency scan reports her baby has a 1 in 200 risk of Down syndrome the pregnant woman is typically very anxious about the result and usually doesn’t want to accept that degree of risk but wants to make sure all is ok by having an amniocentesis. So it is easy to understand that she is more likely to want an elective Caesarean section as there is a 1 in 200 risk of a ruptured uterus and all its implications and risks to her and her baby’s wellbeing with attempting a VBAC.

- Obstetricians take less risk with childbirth today than in the past in all sorts of scenarios. For example, obstetricians are discouraged from doing breech vaginal deliveries today as it is documented that they are much more risky for the baby than Caesarean section delivery. Obstetricians are discouraged from doing the difficult forceps they did in the past, as there is too much associated risk for the mother and baby.

- Society is less tolerant of risk generally, and tends to choose the safest options. As well, there is more and more legislation on this theme e.g. swimming pool fences, correct fitting of baby car capsules, wearing seat belts in cars, etc. etc. When something adverse happens the usual question is “how can we avoid this happening again?” In this case if a woman has a uterine rupture the first question is: “was this avoidable?” The answer is: “yes”. The second question is” “how we can avoid this happening again?” The answer is: “an elective Caesarean section”. Obstetricians have told me women they have managed who have had uterine rupture in labour have said if they could have done it again they would have had an elective Caesarean section rather than attempting a VBAC.

- Elective Caesarean section has become more popular. There are now women who want a ‘Caesarean section by choice’, even though there are no obstetric indications.

- Risk of litigation. In the past in Australia there was far less litigation and the community accepted adverse outcomes as ‘something that happens’. This has changed. Today if a woman has a ruptured uterus then it probable she and/or her family or friends will want to hold her obstetrician as well as hospital staff responsible. I personally know obstetricians who have been sued by patients who have had ruptured uterus.

Many women are wavering

I believe pregnant women don’t want to put their personal wellbeing and their baby’s wellbeing at risk. I also believe most want to experience labour and delivering a baby vaginally. Many see part of ‘being a woman’ is to be able to bear children, labour and deliver babies vaginally.

I believe pregnant women don’t want to put their personal wellbeing and their baby’s wellbeing at risk. I also believe most want to experience labour and delivering a baby vaginally. Many see part of ‘being a woman’ is to be able to bear children, labour and deliver babies vaginally.

Another reason I hear why a woman is inclined to a VBAC attempt is she felt there was less opportunity to ‘bond’ with her baby when she had her Caesarean section. She may comment her baby ‘was rushed away’ by the nursing staff. This is more likely if she has an emergency Caesarean section and especially if there was concern about baby’s wellbeing at the time. It should not happen with an elective Caesarean section unless there is concern about baby’s wellbeing which is less likely or unless the nursing staff are very busy. At the Sydney Adventist Hospital, there can be ‘baby-friendly’ Caesarean sections, which means the midwife and the baby stay with the mother and her husband/partner while she is in theatre and recovery ward.

Another reason I hear why a woman is inclined to a VBAC attempt is because she associates a Caesarean section with a more protracted recovery, being less mobile and less able to look after her baby and her other child/children. She associates a vaginal delivery with a better recovery. Indeed this will be the case if all goes well. But she is more likely to have a more difficult recovery if she has a ruptured uterus or if she needs an emergency Caesarean section for another reason (which is the case for about 38% of women who attempt a VBAC) or if she has significant vaginal/perineal trauma with a vaginal delivery.

Recovery after an elective Caesarean section is usually better than after an emergency Caesarean section. One reason for this is the woman is not tired before having an elective Caesarean section. A failed VBAC Cesarean section is done usually after hours of labour and so she is often tired when her baby is delivered. The circumstances that result in the need for an emergency Caesarean section can be very worrying, the Caesarean section won’t be family or baby-friendly and she may need to have general anaesthetic because of the circumstances. All these factors can have a negative impact on her postnatal recovery. As well with an elective Caesarean section, she knows she will be having a Caesarean section delivery and so she does not have the psychological disappointment of having failed a VBAC delivery attempt. Other variables are actors peculiar to that first Caesarean section and surgical technique of the obstetrician or trainee obstetrician who did the operation. As a general rule, my patients do extremely well and can go home three or four days (their preference) post-delivery and can be driving their cars well before their six-week postnatal visit. A Caesarean section does not have to have a more protracted recovery and interfere with her looking after her baby and her other child/children.

Which path a woman goes down is a difficult call for her to make. It there are factors that increase her risk of uterine rupture with an attempt at a VBAC then it’s an easier decision for her to opt for an elective Caesarean section. But if not, she will need to make the decision. If she decides on an attempt at a VBAC she will only know retrospectively that she made the right call.

My personal experience and attitude

Over many years I have managed many thousands of women in labour and have delivered thousands of babies. I have managed hundreds of women in labour who have had previous Caesarean sections.

I have never had a patient rupture her uterus while in my care.

It is not to say a uterine rupture won’t happen to one of my patients.

I consider my good track record has a lot to do with me being very diligent in my management and taking all appropriate precautions to increase safety and reduce risk. But the unpredictability and attempted VBAC labour ending as a ruptured uterus makes me (and the midwifery staff) very anxious until after the baby is safely delivered.

Also see the RANZCOG College ‘Statements & Guidelines’ on Planned Vaginal Birth After Caesarean Section (Trial of Labour) (C-Obs 38)