This is a common question.

When I was training to become an obstetrician most women who had a Caesarean section had a vaginal delivery next pregnancy.  This has changed. Now most women who had a Caesarean section have a Caesarean section next pregnancy.

This has changed. Now most women who had a Caesarean section have a Caesarean section next pregnancy.

There are several reasons for this change

- Caesarean sections are now safer, more available and more popular.

While the basic surgical techniques are the same there are now better suture materials, better drugs to contract the uterus faster and stronger after delivery (less haemorrhage), the introduction of prophylactic measures to prevent infection and minimise the risk of deep vein thrombosis and so now Caesarean sections are surgically safer than in the past.

Anaesthetic drugs and techniques for Caesarean sections have also improved and so anaesthetics are safer for woman than in the past. This is especially because of the introduction of epidural and then spinal regional anaesthetics.

With effective regional anaesthetics for Caesarean sections a woman is awake and can see and touch her baby immediately after delivery. As well with the introduction of ‘family friendly’ or ‘baby friendly’ Caesarean sections the baby and her husband/partner stay with her in the operating theatre and in the recovery ward. This has resulted in the operation not only being much safer but a much more positive experience.

There has been a consequential increase in popularity for the above and other reasons. When I was training to become an obstetrician no more than 10% of deliveries were by Caesarean section. Now over 40% of all deliveries are by Caesarean section in the hospitals where I have appointments.

Now the risk of attempting a vaginal delivery after a Caesarean section is more dangerous than a repeat Caesarean section.

- Patients now are more risk adverse today than in the past.

When asked the question: “Will I need another Caesarean section?” it is usually followed by a second question: “What is safer for me and my baby?” The answer is: “A repeat Caesarean section.”

I discuss the risk of uterine rupture in labour, what would happen if it did happen, it’s possible adverse consequences for mother and baby’s wellbeing. I also mention that uterine rupture is retrospective diagnosis and cannot be anticipated before it happens.

I mention the incidence varies from one study to another, but it is usually considered the incidence is about 1 in 200. RANZCOG reports the incidence as between 1 in 142 and 1 in 200 (1). As well I mention that only 60% of women who attempt a vaginal delivery after a Caesarean section are successful in having a vaginal birth (1). The other 40% end up with an emergency Caesarean section for various reasons.

I also advise that an elective Caesarean section in today’s times is safer for mother and baby.

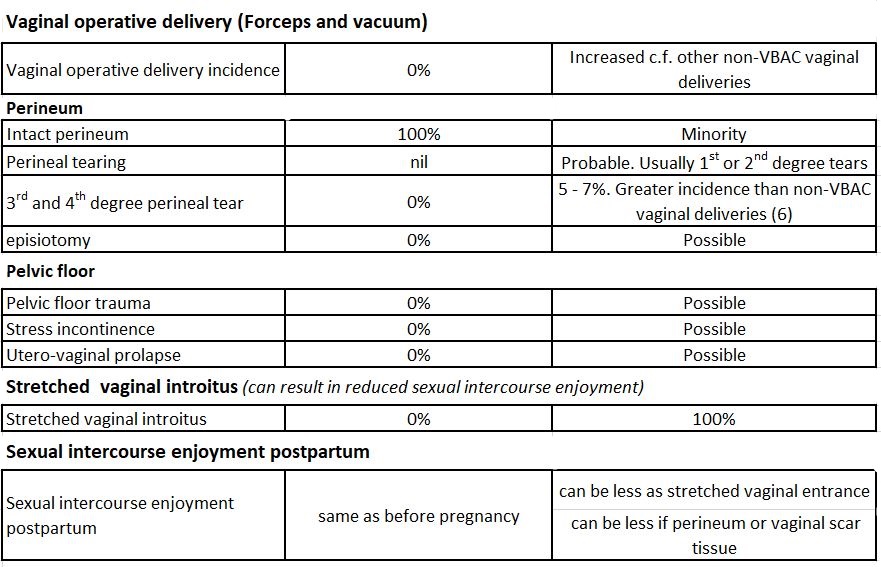

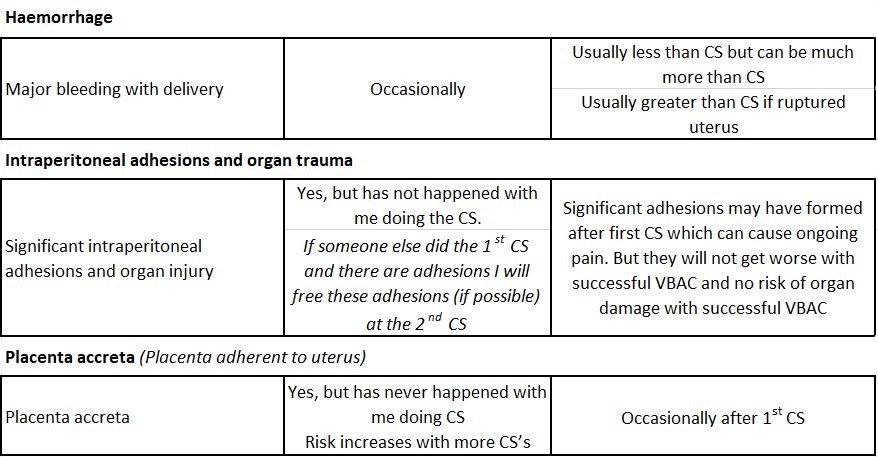

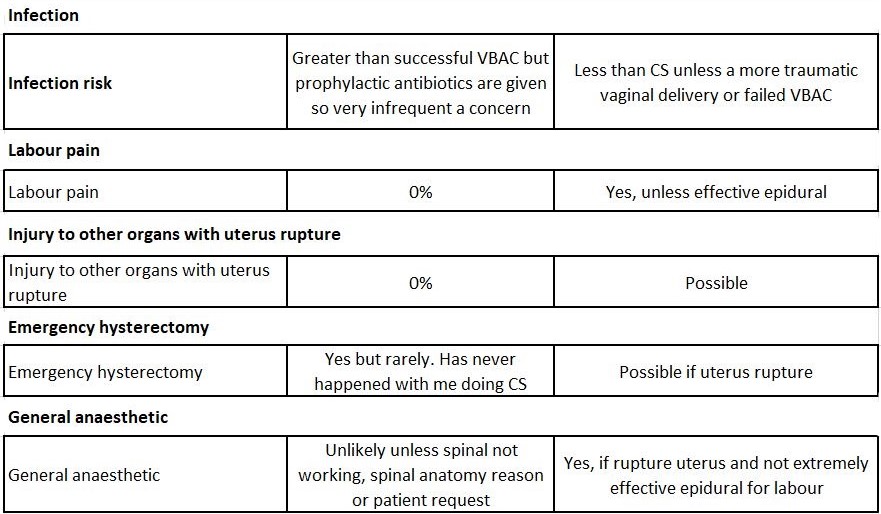

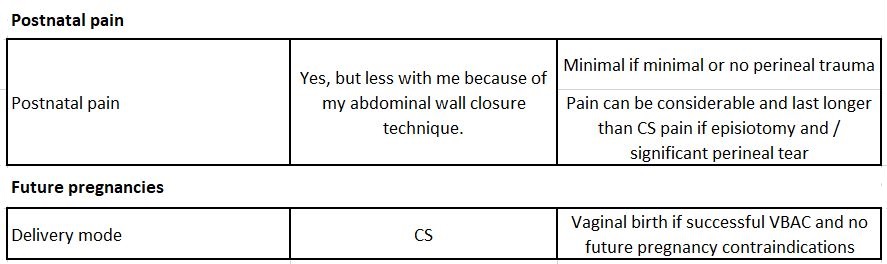

There are many other points of difference, which I discuss with patients. The points of difference between repeat Caesarean section and attempting a vaginal birth are summarised in the table at the end of this article.

This concern about a 1 in 200 risk of uterine rupture is consistent with the response women give if they have had a NTS (nuchal translucency scan) and are told the risk of baby having Down Syndrome is 1 in 200. They usually will accept this Down Syndrome risk and want an amniocentesis (or now a NIPT (non-invasive pregnant test)) to check.

In the past, when I was training to become an obstetrician and in my first years as a specialist obstetrician, I recall people were less risk adverse. In the past backyard pools did not have fences, there were no restrained baby seats in cars, kids walked to school by themselves, kids on bikes did not wear helmets, etc, etc. While legislation has improved safety, many people are now, compared to in the past, more fearful of what can go wrong and are less inclined to accept anything that results in an increased risk of an adverse outcome.

In the past there was much less discussion and concern about uterine rupture risk. There was an extremely low incidence of medical litigation and the doctor’s advice was accepted. But the pregnant women in the past did know there was risk of uterine rupture in labour. Attempting a vaginal birth after a Caesarean section was in the past was called a ‘trial of scar’ labour. It was a trial to not only achieve a vaginal outcome but also that scar from the previous Caesarean scar remained intact. Now the fashionable term is attempting a VBAC (Vaginal Birth After Caesarean). I do not agree with the term VBAC as it hides the risk of uterine rupture and its implications. I wish we still called it a ‘trial of scar’ labour now so there was no misleading and no confusion about the implied risk.

In the past not only was the incidence of Caesarean section much less (10%), but my recollection is women who had a previous Caesarean sections had ‘trial of scar’ labours unless the previous Caesarean section was done for a reason that was likely to be relevant this time, when attempting a vaginal birth was considered too dangerous. Back then Australia and the UK had a very different attitude to the USA where it was popularly considered “once a Caesarean always a Caesarean”.

When I was training to become an obstetrician most Caesarean sections were done under general anaesthetics. To avoid a general anaesthetic was another motivation for attempting a vaginal delivery.

My recollection is the majority of ‘trial of scar’ labours were successful and far less than 40% of women needed an emergency Caesarean section in labour. My recollection is the incidence of uterine rupture was less than 1 in 200. One Australian obstetric textbook written in 1969 has lower uterine scar rupture incidence as 1 in 400 (2).

I suspect there was a lower incidence of uterine rupture in the past because obstetricians and trainee obstetricians were more careful in closing the uterus. I was trained to close the uterus in three layers (and I still do this now). Now many obstetricians and trainees close the uterus in one layer only, which has an implied increased risk of a weaker scar and increased risk of uterine rupture.

Personally, I have managed many women over many years with ‘trial of scar’ labours and have never had a ruptured uterus.

- Litigation concerns.

In the past “suing the doctor” rarely happened. Patients attitude was their doctor did their best and patients accepted that occasionally things went wrong. If something goes wrong, they did not usually blame the doctor. The doctor’s management advice as to what should be done was not usually questioned. This is not the case now. There has been a gradually increasing incidence of litigation against doctors. If something does go wrong or even if the patient is dissatisfied with care but all went well, then the patient of her own volition or because of the encouragement of family, friends or social media or lobby groups with vested interests decides to sue the doctor.

This increased incidence of litigation is encouraged by ‘ambulance chasing’ law firms with their ‘no win no pay’ advertising. But what these law firms do not say up front is if you do win, they will keep a very significant amount of the payout. I have a patient for her third pregnancy management who successfully sued a main public teaching hospital she attended for her second pregnancy management after an avoidable ruptured uterus and grossly mismanaged labour. The payout was less than I suspected, and the law firm kept about half the money.

I remember when I was an obstetrics registrar when hearing that in the USA “once a Caesarean section, always a Caesarean section’ saying to colleagues this would never happen here. This attitude in the USA had to do with the high incidence of litigation. As the incidence of litigation increased in Australia, we started going down the same high repeat Caesarean section rate pathway.

Doctors’ medical indemnity premiums have exploded because of increased litigation. When I first started, I was only paying few hundred dollars per year in medical indemnity premiums. Now it is many tens of thousands of dollars per year, and it would be more except for the intervention of the Howard Federal Government.

This increased litigation has resulted in a change in patient health care attitude. Doctors are now more ‘risk adverse’ and are more likely to recommend management that is less likely to result in litigation irrespective of whether this is the most appropriate management for the patient.

A colleague had a patient where her uterus ruptured in labour. He said he knew the patient well over many years and thought he had a good relationship with her. It was a small tear that he was able to easily repair. It was a good outcome for mother and baby. But she still sued him. He was absolutely devastated.

There is now considerable emphasis on ‘informed consent’, so if something does go wrong the patient is less likely to sue and litigation is much less likely to be successful. But all medical procedures have risk and patients can get scared of being told such adverse outcomes as they often cannot filter the risk assessment. Obstetricians are now encouraged, and some hospitals insist (3), patients sign an informed consent before attempting a vaginal birth after a Caesarean section. When asked to do so most decline as while they want a vaginal birth, they do not want to accept responsibility for their decision and of a uterine rupture should it occur. They usually decline and decide on a Caesarean section.

- Patient choice

As mentioned in the past patients usually accepted without asking questions, their doctor’s decision as to what appropriate management would be. Today with the internet, and social media and various lobby groups there is a lot information and opinions from other sources that may or may not be accurate, but which encourages patients to ask questions and to have more detailed discussions with their doctor and also sometimes seek a second opinion if they don’t agree with their doctor’s decision.

Patients are encouraged to be more proactive in decision making. There is much more detailed discussion of options of care, risks and benefits, etc. which is a good thing.

While patients want to make their own decisions in their care they usually do no want to accept responsibility for adverse outcomes that may occur because of their decisions. They want to blame the doctor if something goes wrong. “If the doctor had told me this could happen I never would have…”

A ruptured uterus can have devastating consequences and if this happens the patient will usually want to blame the doctor and not accept responsibility for her decision to attempt a vaginal delivery. On the flipside I have a patient mentioned above for management of her third pregnancy who wanted a repeat Caesarean section in her second pregnancy. She was being managed as a public patient in her second pregnancy and the public hospital staff refused to agree. I suspect they were motivated by the NSW Department of Health policy and midwife pressure. She had an attempt at vaginal delivery, which she did not want, and her uterus ruptured in labour.

Guidelines for attempting a vaginal birth

A number of years ago these were introduced by the College (RANZCOG). While abiding by these guidelines increases the incidence of repeat Caesarean section it also increases the delivery safety for mother and baby .

I discuss these guidelines with patients and if she does not fall within the guidelines, I strongly advise a Caesarean section.

The RANZCOG advises the risk of a uterine rupture increases in the following circumstances:

- Previous classical or vertical lower uterine segment incision.

- Previous myomectomy (fibroid removal).

- Previous rupture or perforated uterus at a gynaecology operation.

- More than one previous Caesarean section.

- Labouring less than 18 months since the previous Caesarean section.

- Morbid maternal obesity (BMI (Body Mass Index) >40).

- Foetal weight > 4 kg.

- Contracted (small) pelvis.

- Labour with other than a cephalic (head down) presentation of baby.

- Poor uterus cut surgical closure technique of the obstetrician who did the previous Caesarean section.

- Poor healing of the previous Caesarean section uterus cut.

- Induction of labour.

- Augmentation of labour if slow progress in labour.

If any of these items are relevant the pregnant woman is advised she should have an elective repeat Caesarean section.

Repeat Caesarean section and attempting vaginal birth after a Caesarean section comparison table

Also see VBAC – Risks and management

- https://ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical-Obstetrics/Birth-after-previous-caesarean-section-(C-Obs-38)-_-Jan-2022.pdf?ext=.pdf

- Fundamentals of Obstetrics & Gynaecology Derek Llewellyn -Jones

- https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/kidsfamilies/MCFhealth/maternity/Pages/consent-req-pregnancy-birth.aspx

- https://www.smh.com.au/healthcare/after-five-years-of-towards-normal-birth-in-nsw-are-mothers-better-off-20150724-gijhxu.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2922912/#R26

- https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.17063 and https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/2016/05001/Is_There_a_Higher_Incidence_of_Obstetric_Anal.116.aspx